Country ‘ready’ to intervene after currency (ringgit) hits lowest level since Asian crisis

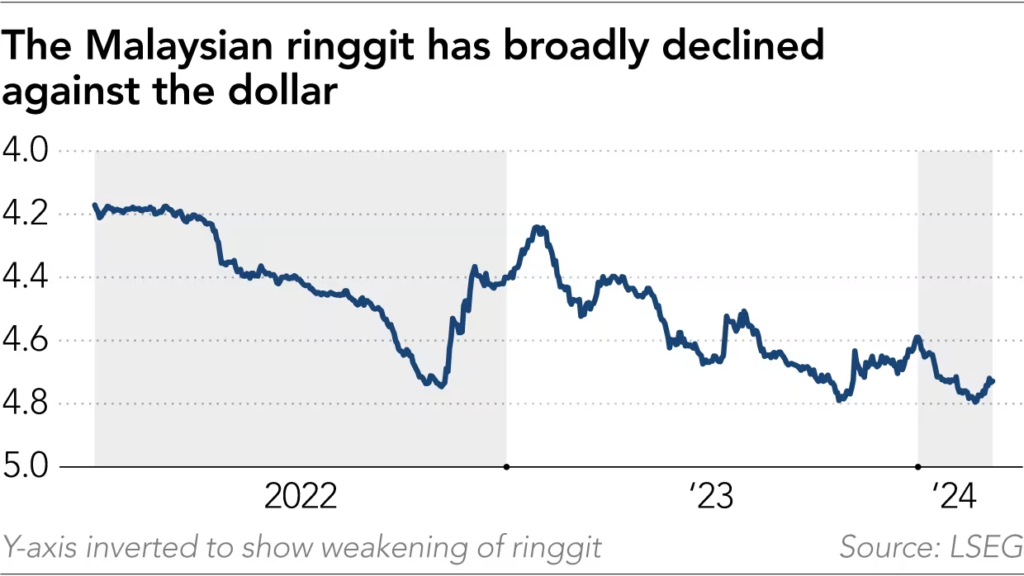

KUALA LUMPUR/SINGAPORE — The beleaguered Malaysian ringgit is testing levels not seen since the depths of the Asian financial crisis more than a quarter century ago, causing officials to step up their rhetoric to try and stem the slide.

The ringgit hit a 26-year low of 4.7965 to the greenback on Feb. 20. Three days later, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim called the decline “concerning,” but “under control.” Then on Feb. 29, a top Finance Ministry official said Bank Negara Malaysia, the central bank, is prepared to defend the ringgit by selling some dollar reserves.

By March 8, the ringgit had clawed back some gains, rising to 4.682 against the dollar, but authorities have stressed that their currency should be stronger, given the Southeast Asian country’s improving economic outlook. And although the ringgit is showing signs of stabilizing, analysts expect it to remain weak for the time being as it remains unclear exactly when the U.S. Federal Reserve will begin cutting interest rates, though such a move is expected this year. That would likely help relieve downward pressure on the ringgit and other emerging-market currencies.

The ringgit’s recent trough approached the 4.8850 mark hit on Jan. 7, 1998, a level fraught with symbolism for Malaysians. Malaysia, led by then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, took major steps, including the imposition of capital controls, to insulate itself from the regional financial turmoil that had decimated the Thai baht, the Indonesian rupiah and the South Korean won the previous year.

Weakness of the Ringgit

And while officials and analysts are quick to dismiss comparisons to the crisis years of the late 1990s, the ringgit’s current weakness is still a major concern. The government is keenly aware of the economic impact on consumers.

“If the ringgit continues to depreciate, this could stoke renewed inflationary pressure, which is something that Bank Negara Malaysia would wish to avoid,” Richard Bullock, portfolio manager of the fixed income team at Newton Investment Management, told Nikkei Asia.

With U.S. interest rates at a 23-year high, capital has fled Malaysia as investors seek better returns elsewhere. They expect the Fed to start lowering its benchmark rate in June, as U.S. policymakers seek more evidence that inflation is firmly on a downward path before cutting rates. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell told the Senate Banking Committee on Thursday that U.S. monetary authorities were “not far” from having sufficient confidence in falling inflation to start reducing rates.

Policy Makers

Malaysian policymakers, for their part, are trying to draw capital back home. On Feb. 29, Second Finance Minister Amir Hamzah told parliament that there would be “an intensified coordination” between the government and the central bank to urge state-linked firms to repatriate foreign investment income and convert it into ringgit “more consistently.”

The policymaker added that the central bank is “always ready” to curb the ringgit’s volatility and is prepared to sell dollars from its reserves to “restrict excessive weakness in the ringgit.”

In response to the minister’s remarks, Bank Negara Malaysia’s Financial Markets Committee said there had been an “immediate impact on market flows, and increased market interest in buying ringgit.”

The central bank has repeatedly attributed the fall in the currency to external factors, including U.S. interest rates and an uncertain Chinese economic outlook. The ringgit is undervalued, authorities say, and does not reflect the country’s positive economic prospects.

As an export-driven country, a weaker currency would typically benefit the economy. But that also means higher costs for importers, raising prices of goods and services.

“For Malaysians, the most serious effect is inflation, especially the cost of food due to high imports,” said Bridget Welsh, honorary research associate with the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute Malaysia.

Malaysia has factors in its favor compared with the crisis days of the late 1990s, when it had a current account deficit of close to 5% of gross domestic product. That proved unsustainable, and the government could no longer maintain a managed currency float, resulting in a one-off devaluation of 50%.

Now Malaysia is running a structural current account surplus of between 2% and 3% of GDP, a positive for the currency. “The Malaysian economy is in a much stronger external position, with better functioning financial markets now,” said Charu Chanana, head of foreign exchange strategy at Saxo.

Still, the ringgit has been the weakest currency in Southeast Asia over the past year. While other regional currencies have also been affected by China’s economic slowdown and high U.S. interest rates, the Indonesian rupiah and Vietnamese dong have depreciated less than the ringgit against the dollar.

For Malaysia, slowing global demand is weighing on the country. Its current account surplus was 253.4 million ringgit ($54 million) for the October to December quarter, narrowing 97% from the previous three months, official data showed on Feb 16. A narrower surplus puts downward pressure on the currency as less capital flows into the country.

Bullock at Newton Investment Management said Malaysia’s terms of trade, a measure of a country’s export prices relative to its import prices, have been falling steadily over the past year and a half as the relative value of the country’s commodity exports, such as palm oil, has declined.

Toru Nishihama, chief economist at Japan’s Dai-ichi Life Research Institute, meanwhile, says that despite Malaysia’s external balance being robust, the “public debt level is relatively high among Asian emerging economies, while its fiscal position continues to deteriorate since the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Looking ahead, analysts expect the ringgit to bounce back.

Rebound Forecast

On Feb 22, S&P Global Ratings sovereign analyst Yee Farn Phua forecast a 9% rebound in the ringgit, saying the bout of weakness does not pose a risk to the country’s sovereign rating. Local think tank MIDF also expects the currency to appreciate, benefiting from greater capital inflows. It predicts the ringgit’s average value in 2024 will rise to 4.38 versus the dollar and reach 4.20 by year’s end.

“[The] ringgit is likely to recover later in the year, especially as Fed rate cuts drive the dollar lower,” said Chanana at Saxo. Fitch Solutions’ BMI echoed that sentiment, saying that as the Fed eases in the second half of 2024, yield differentials are expected to “gradually favor the ringgit” and bolster its value.

Geoffrey Williams, an economics professor at Malaysia University of Science and Technology, concurs.

“We expect the worst is over. The ringgit will trade normally now and will likely appreciate during the year as we become clearer on global trends and move closer to Fed rate cuts,” Williams said.

Additional reporting by Hakimie Amrie. – Nikkei Asia

Editor’s Note: Article above was first published in Nikkei Asia.

New Malaysia Herald publishes articles, comments and posts from various contributors. We always welcome new content and write up. If you would like to contribute please contact us at : editor@newmalaysiaherald.com

Facebook Comments