Rising food prices and weak currency hamper reform plans of PM Anwar

KUALA LUMPUR — In San Francisco last week, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim was eagerly promoting his country, known as a Southeast Asian manufacturing hub and major commodity exporter.

“Malaysia and ASEAN are the most stable and vibrant places to invest, and I look forward to meeting you individually in Malaysia,” he said at the APEC CEO Summit. “I think we are on the right track to propel the economy of our country in the next few years.”

But as his government marks its first anniversary this week, political observers say mounting challenges may pose hurdles for Anwar to achieve economic and fiscal reforms that are necessary to create a more robust environment for the country’s future growth.

Meeting with representatives from tech giants such as Google, Microsoft and TikTok during the U.S. trip, he expressed Malaysia’s commitment to providing a speedy approval process for all investors.

“Hopefully, the meeting with all these giant companies can bring benefits to the country and the people as a whole, God willing,” he wrote on Facebook.

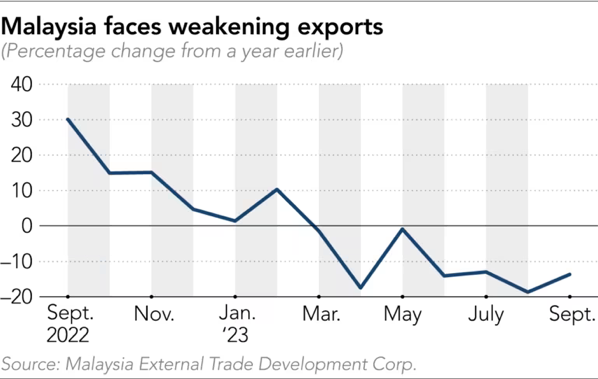

However, the domestic economy faces headwinds. The July-September gross domestic product data released last Friday showed that exports declined 12% from a year earlier, weighing on overall growth. Rising food prices and the falling ringgit currency, which hit a 25-year low last month, have also affected many businesses and households.

Anwar, a longtime opposition symbol who is now 76 years old, became Malaysia’s 10th prime minister on Nov. 24 last year after his Pakatan Harapan coalition won the general election that month. Forming a ruling coalition that he calls the “unity government,” he promised institutional and economic reforms.

Anwar 5th PM in less than five years

Malaysia had been politically unstable for years. Anwar is the fifth prime minister in less than five years, after Najib Razak (2009-2018), Mahathir Mohamad (2018-2020), Muhyiddin Yassin (2020-2021) and Ismail Sabri Yaakob (2021-2022). As such, Anwar’s victory raised hopes for a period of stability and progress at a time when Malaysia was recovering from the pandemic.

“For the first time I see a prime minister that Malaysia can be proud of when he goes overseas. He raises the name of the country,” said Kishan Buxani, a 26-year-old voter from Penang.

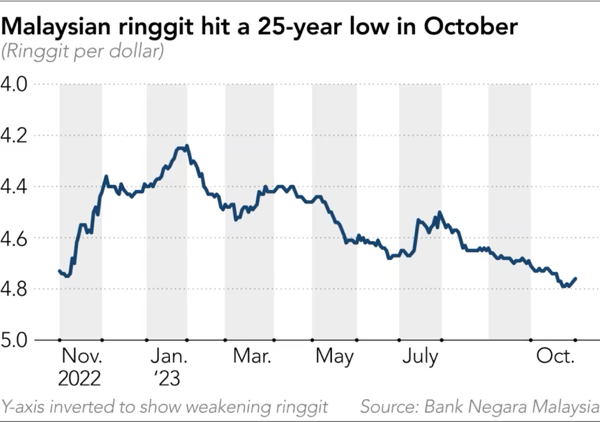

Indeed, there was a sense of a breath of fresh air when Anwar first took office. The stock market rallied in the first few months, and the ringgit strengthened to 4.24 per dollar in February. According to the local pollster Merdeka Center, Anwar enjoyed a high approval rating of 68% in that month.

However, Anwar’s first year has been a balancing act, with the prime minister grappling with economic woes, political tensions and the lingering effects of the pandemic while striving to deliver on his ambitious reform agenda.

The government has introduced the New Industrial Master Plan 2030, which includes a target of boosting the manufacturing sector’s GDP by 6.5% annually through 2030, and the National Energy Transition Roadmap, which seeks to restructure the economy, achieve sustainable growth and ensure an equitable distribution of wealth.

Statistics show some positive developments in his first year. The government received 132 billion ringgit ($28 billion) of direct investment in the first half of 2023, achieving 60% of this year’s target of 220 billion ringgit. According to the local think tank MIDF Research, the unemployment rate maintained a post-pandemic low of 3.4% in September, with the youth unemployment rate falling to 10.6%.

Statistics show some positive developments in his first year. The government received 132 billion ringgit ($28 billion) of direct investment in the first half of 2023, achieving 60% of this year’s target of 220 billion ringgit. According to the local think tank MIDF Research, the unemployment rate maintained a post-pandemic low of 3.4% in September, with the youth unemployment rate falling to 10.6%.

Global Economic Downturn

But Anwar’s government was not spared from the global economic downturn. The World Bank in October downgraded Malaysia’s economic growth for this year to 3.9% from an earlier projection of 4.3%, compared to 8.7% in 2022 and the pre-pandemic years’ 4% to 5%, citing a significant slowdown in external demand.

The ringgit is the worst-performing currency in the region this year, falling by more than 5% against the greenback and hitting its lowest value in 25 years, at 4.792 per dollar, on Oct. 23. About 4.19 billion ringgit flew out of the Malaysian equity market during the first half of 2023, according to MIDF Research.

“As an oil exporting country, exposure to oil price shocks and vulnerability to sudden and sizable capital outflows are the main factors that likely explain why the Malaysian ringgit stands apart” compared with other Asian currencies, the World Bank said in the October report. Economists say a widening interest rate gap with the U.S. and the slowing economy of its key trading partner, China, are also among the factors in the ringgit’s depreciation.

Several business owners and small traders in Kuala Lumpur told Nikkei Asia that the weak ringgit has affected their supply of food items and other goods and increased overhead costs due to their dependence on imported goods, equipment and services, adding to the global inflation that has in turn affected Malaysia.

Small Businesses Affected

Wong Mee Fang, a 70-year-old owner of a vegetarian food stall in the city of Petaling Jaya, west of Kuala Lumpur, says the rising costs of rice and other materials have severely affected her business, forcing her to raise prices. The retail price of imported rice was raised 36% in September, reflecting a global price surge.

“Business has been rather uncertain. It is more difficult for vegetarian food stalls like mine,” Wong told Nikkei Asia. “I know the government is trying [to address food inflation], but the rising food prices over the past year have affected many of us, especially small businesses like ours. I’m not sure how long I can continue.”

While these economic issues have caused dissatisfaction among Malaysians, Anwar is also feeling pressure on the political front.

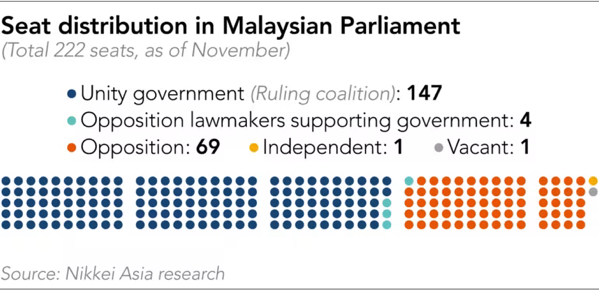

Currently, he enjoys support from two-thirds of the members of the 222-seat House of Representatives, including 147 from the ruling coalition and four opposition lawmakers who recently announced they will support his government.

But local elections held in six of the country’s 13 states in August resulted in a blow to the prime minister, with the ruling coalition losing about 30% of its state assembly seats. The Islamist and right-leaning opposition party Perikatan Nasional increased its inroads into his coalition’s strongholds.

Bridget Welsh, an honorary research associate at the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute Malaysia, explained that the outcome of the state elections highlighted his weakness among Malay voters and placed his government at risk of losing its non-Muslim base that voted for tolerance and moderation.

“Few recognize him as a reformer, and even fewer see a commitment to reform in his first year,” Welsh said, adding that the current political stability was achieved at the cost of any meaningful reform and a betrayal of trust. In September, the country’s authorities dropped corruption charges against Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, the leader of a key partner in the ruling coalition, which raised questions over Anwar’s pledge to fight corruption.

“Anwar was supported for what people believed to be statesmanlike leadership and the hope for a clear vision of governance for the country. Neither have yet to materialize. A focus on trying to look good personally rather than actually laying out a clear program and governing has hurt Anwar’s government performance,” Welsh added.

Anwar’s government did introduce several reforms, including the repeal of the mandatory death penalty, decriminalization of suicide attempts, and rationalization of government agencies and departments to improve efficiency.

Anwar, who doubles as the finance minister, last month vowed his commitment to fiscal reforms. “Hence, reforms need to be implemented, notwithstanding that it may be an arduous and challenging process,” he said in his speech for the 2024 draft budget, referring to expanding the revenue base, implementing targeted subsidies and eradicating corruption and malpractice.

As his government enters its second year, Anwar must start delivering on his promises more, according to James Chin, a professor in Asia studies at the University of Tasmania.

“A lot of people don’t believe that he can do it, and that is why you can see the fall of the ringgit and you see the stock market is restless,” he argued. “He has to put in policies that will pay off in one or two years’ time. So time is running out for him.” – Nikkei Asia

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Nikkei Asia on November 21 2023.

New Malaysia Herald publishes articles, comments and posts from various contributors. We always welcome new content and write up. If you would like to contribute please contact us at : editor@newmalaysiaherald.com

Facebook Comments